Contaminating the Preserve

Background

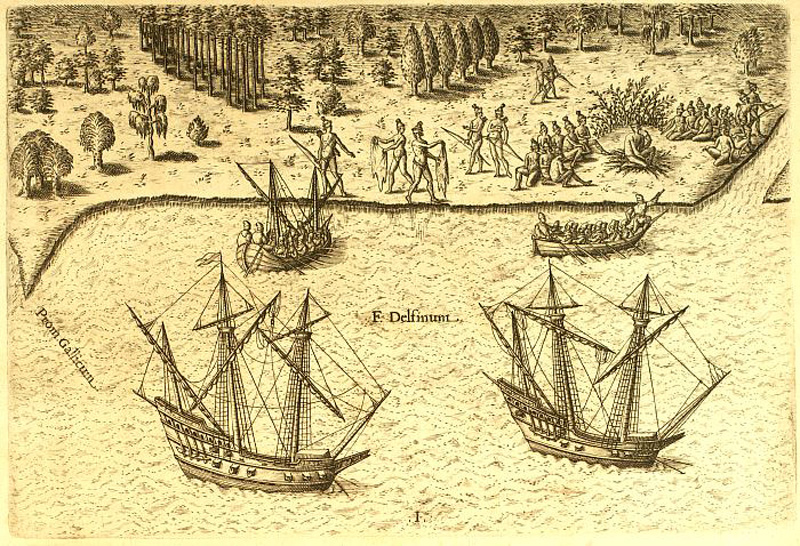

Founded in 1988, the Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan, following more than 60 years of effort by people wishing to celebrate the European discovery of La Florida. The preserve’s original boundaries enclose 47,000 acres of Northeast Florida, a vast tract of ecosystems managed by federal, state, city and private landholders. Some of the key sites included within the preserve include: a slightly scaled down model exhibit of the French Fort Caroline, a reproduction of a monument to French entrepreneur and colonist Jean Ribault, Kingsley Plantation – one of the most intact examples of the slave plantation system from the 18th-19th centuries, and vast tracts of Florida wetlands and forests with hiking trails. The Preserve is named for the cultures that inhabited the area at the time of French and Spanish arrival, the Timucua.

Defining the Problem

The Timucuan Preserve, as a set of non-contiguous territories and historically disparate narratives, has the potential to educate and embody principles of environmental and social justice on a fairly large scale. The Travel Office has primarily worked to identify the ideological and institutional barriers that prevent the Preserve from serving a more diverse audience (at local, national and international scales) and from playing a more active role in addressing ongoing social and environmental problems of the region. Our research led us to the conclusion that the Preserve’s historical and ecological mission was overly defined through narrow notions of preservation. Relevant history was determined through conventional ideas about linear trajectories of development, from the inevitability of European conquest to white settler land stewardship. Likewise, ecology is presented through modern notions of resource management and ongoing desires for a wilderness escape from modern civilization. These ideological imperatives prevent the Preserve’s administration from addressing a complex of histories and ecologies that exist within it and surround it. It is our position that these ignored histories and ecologies present opportunities to both better understand those histories already acknowledged in the Preserve and open its preservationist and educational mission to populations and communities excluded from its purview.

Outcomes + Results

During our ongoing consultancy, we have developed a series of proposals that identify some specific opportunities for redirecting the historical and ecological imperative of the Preserve. The proposals exist only as propositions, and include absurdist provocations and potentially viable projects. One of these proposals is described below. Our ideal outcome would be the realization, even in temporary form, of the more practical propositions within the Preserve itself and a public presentation of the provocations as a means for instigating discussion about the topics they address. For more existing proposals see:

http://temporarytraveloffice.net/jax/audioTour.html

Proposal Sample (a practical proposal):

Ash Site Annex

The proposed Ash Site Annex (ASA) to the Preserve introduces yet another series of narratives hitherto considered outside of its historic and ecological scope, yet closely linked by geography, history and a sense of environmental awareness. The ASA takes a cue from the Preserve’s celebration of the “Timucuan Indian” cultures of Northeast Florida – referred to as “People of the Shell Mounds.” This nickname is derived from the vast amounts of shellfish remains they left along the river we call the St. Johns. The Timucua were extinct by the middle of the 18th century – two hundred years of colonial wars and introduced disease effectively decimated the tens of thousands that existed at the time of European contact. As the National Park Service states:

The lesson to be learned from the existence and disappearance of the Timucuan people is that in a clash of cultures ultimately one group, no matter how advanced or well established, may vanish.

In essence, the ASA asks: If Jacksonville’s current residents were to vanish, what kinds of stories would we be found in our trash? What kinds of mounds would we be the “People of”? And, what kind of “clash of cultures” would be found?

We will jump ahead from colonial conquest to the late 1920s to begin to answer these questions. Between 1928-1929, the administration of then Jacksonville Mayor John T. Alsop decided that the city would be divided into six districts, and that they should “locate colored districts adjacent to incinerators.” Incineration, or burning, was an attractive method for dealing with the growing mounds of solid waste following in the wake of industry-led developments of disposable products and packaging.

Rediscovered in the early to mid 1990s by the Florida Dept of Enviro Protection (FDEP), the Jax Ash Site boundaries contain 3 separate sites known to be waste incinerators and dumps that were used by the City of Jacksonville from the late 19th century into the 1960s.

There are 6 other ash-related contaminated sites in the vicinity of the Jax Ash Sites, under the responsibilities of the FDEP and the US EPA. This makes 9 ash-related sites in the same general vicinity of Northwest Jacksonville, adding up to more than 321 acres of ash contaminated land.

Of those 9 sites, 3 are near or within city parks and 2 had public schools that were closed in the last 5 years or less following community outcries and some media coverage. As is common across the US, these contaminated sites rest under communities that are predominantly African-American and economically depressed.

These incinerators burned all manner of solid waste, producing ash containing lead, arsenic, dioxin, PCBs, mercury, and pesticide compounds. This ash material became airborne, drifting in, and beyond, the mostly African-American neighborhoods where the incineration occurred. During the 1950s and 1960s, Jacksonville’s incinerators were shut down, but as we will see, they continue to impact many lives.

Why Implement An Ash Site Annex

The Travel Office’s vision of the Ash Site Annex is predicated on the concept of “environmental preservation districts” and “environmental reparations” put forth by environmental justice scholars Robin Morris Collin and Robert Collin. Being that the Preserve is not a singularly managed park, but is a collaboration between the National Park Service and “partnership areas” (including the State of Florida, the City of Jacksonville and the Nature Conservancy), the annex does not require handing ownership over to the NPS or any other entity. As the Collins suggest, environmental preservation districts” could function in a similar manner as historic preservation districts, but rather than creating laws to regulate the aesthetics of homes, laws would be used to preserve community and ecological health. This would a step towards “an alternative methodology articulating a new model for historic preservation” called for by scholar Angel David Nieves.